Data Feminism by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein is a literature review and call to action that provides a framework for data scientists and journalists interested in learning a new way of considering data science and data ethics from intersectional feminism stands. This means that their take aims to give people social tools — knowledge and quantitive information to make changes —. They also portray data science as a form of power that, before being used to expose injustice, improve health outcomes, and destabilize governments, was used to discriminate against, police, and surveil underserved communities; scilicet, BIPOC demographics—leading to the questions, by whom? for whom? And whose interests are being served throughout Data science? Unfortunately, the narratives built around big data are predominantly white and male, excluding those who need data the most.

“Data feminism commits to challenging unequal power structures and working toward justice.”

D’Ignazio and Klein demonstrate data feminism by displaying how challenging the cis-heteronormative male and female binary can help challenge other hierarchical and empirically incorrect classification systems that oppress demographics out of the range of power and privilege. They explain how, for instance, understanding emotion can broaden our assertions about compelling data visualization and how invisible labor can accentuate the significant human effort required by our automated systems—referring to the International Feminist Collective’s impact in launching the Wages for Housework campaign to expose the phenomenon of invisible labor — unpaid and thus unvalued labor. Instead, the collective used the term reproductive labor to describe this work, which derives from the monetarist economic distinction between paid and economically “productive” marketplace labor and unpaid and thus economically “unproductive” labor of everything else. By redefining this latter category of work as reproductive labor rather than unproductive labor, feminist movements sought to emphasize the range of tasks covered by the term. For example, cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing were precisely the tasks that allowed those who performed “productive” labor, such as office or factory work, to continue to do so. Still, while white women were unpaid for housework, women of color, particularly Black women in the United States, had long been paid, albeit not well, for housework in other people’s homes.

“Because of the added intrusion of racism, vast numbers of Black women have had to do their own housekeeping as well as other women’s home chores” -Angela Davis.

Housework is structured along gender lines, but it is also structured along race and class lines. As a result, domestic labor performed by women of color was and continues to be under-waged labor, as feminist labor theorists call it. Its low cost enabled and continues to allow many white middle and upper-class women to participate in the more lucrative waged labor market instead. The term invisible labor has come to encompass various forms of unwaged, underwaged, and even waged labor rendered invisible because they occur inside the home, out of sight, or lack physical form entirely. However, as digital labor theorists like Tiziana Terranova have helped us understand, this invisible labor can be found all over the web, “they call it sharing. We call it stealing.” It refers to the work that most of us do daily, such as our Facebook likes, Instagram posts, and Twitter tweets. The point made by Laurel Ptak, the artist behind Wages for Facebook — a point also made by Terranova — is that the invisible unpaid labor of our likes and tweets is precisely what allows the world’s Facebook and Twitter to profit and thrive.

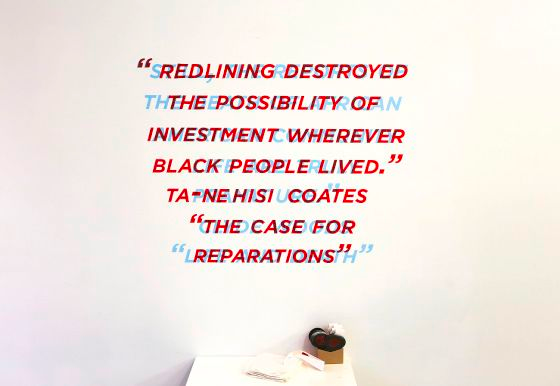

Correspondingly, along race and class lines, they demonstrate why data should never “speak for themselves,” and multiple issues are exemplified. For illustration, mapping, and redlining, a term that echoes the significant racial wealth difference. Redlining is a practice of housing discrimination pioneered by the government decades ago that inhibited investment in Black districts. These neighborhood classifications with a high Black or minority population were frequently marked red or “hazardous,” regarding it dangerous, so banks were deterred from lending to residents in these locations, making it nearly hard for them to obtain the necessary funding to purchase or restore a property. And its consequences may still be felt today. An actual instance of this long-term issue is the deficiency of high-quality public health and education accessibility within neighborhoods of color. Nikole Hannah-Jones, an Afro-American civil rights investigative journalist, explains that health and school segregation are prevalent due to the underfunded public services. The underfund results from property taxes being ought to pay for schools and other public services. In the case of Black communities receiving less investment, the average property value falls, and local hospitals and schools receive less money, resulting in poor life quality and educational performance. Making it more difficult for Black citizens to obtain decent employment, earn more money, and relocate to better communities. And among the solutions, gentrification is put on the table, as well as urban renewal. However, these solutions have overcome any possibilities for Black communities to catch up with the people coming to “improve” their neighborhoods because the impact of racial inequity does not benefit them.

However, on the one hand, people gentrifying and renewing communities of color are primarily white, which, if anything, worsens things due to the financial unbalance. Consequently, what is most likely to happen is that Black families have to displace because the gentrified neighborhoods become costlier for both; renting and property ownership. And on the other hand, no the financial distress being enough, Black communities keep in a constant survival mode meaning that it keeps them socially behind in all aspects. Without dignified homes, the quality of life will not be dignified, including health, education, financial success, and social empowerment. This reinforces the lack of critical understanding of these communities’ struggles.

In summary, D’Ignazio and Klein’s definition of data science includes more than quantitative methods, “big” data, “artificial” intelligence, and “neutral” displays. They explore the limitations of such a limited data science and communication view. They argued throughout the book that an expansive view of data science is required if we are to work toward our goal of remaking the world. And there are numerous other potential starting points for confronting oppression in data from the arts, activism, community organizing, and consciousness-raising, enabling feminist data science to flourish and thrive, deliberate interventions in each phase of data work, and our preconceived notions about the people and communities who perform it will be required.

Citation: D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. (2020). Figure Credits. In Data Feminism. Retrieved from https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/ftb0980j

Previously posted in Medium by Sara Valentina Alvarez Echavarria:

Comments